We all go through something of a sorting exercise in order to make sense out of our experience. It’s part of being human. And in large part, it’s useful and appropriate, allowing us to move through life efficiently. It’s how we take in enormous quantities of data, analyze and synthesize that data, form opinions from the data, and determine a course of action to follow.

Unchecked, however, this sorting process can lead to significant personal and organizational dysfunction. There are a couple of reasons for this. One of the reasons is that we aren’t typically self-aware about the mental framework(s) we use to make sense of things. (Yes, we’re still talking about self-awareness!) The framework we use isn’t itself the problem; our lack of awareness about the framework, how it works on us and others, and its inherent limitations, is where we get into trouble.

Let’s take a closer look.  A useful model for thinking about this meaning-making process is known as the ladder of inference. The concept of the ladder was originally articulated by leadership expert Chris Argyris and later made popular in Peter Senge’s classic business book, The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization.

A useful model for thinking about this meaning-making process is known as the ladder of inference. The concept of the ladder was originally articulated by leadership expert Chris Argyris and later made popular in Peter Senge’s classic business book, The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization.

The ladder of inference refers to the filtering and sorting process by which we accumulate and shape the facts, making interpretations that align with our beliefs. Beliefs are not facts, however. Just like the ideas that drive our fears, beliefs are essentially conclusions we make after applying the filters we have developed over the course of our lifetime.

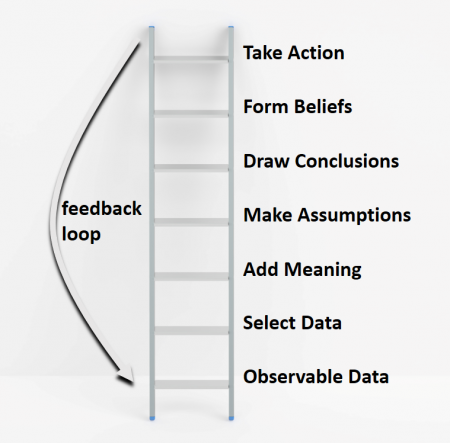

This meaning-making filtering process is dynamic, like climbing a ladder (see image below for a visual). We apply filters to what is objectively observable—what could be seen by a video camera—and move rapidly from objective reality to the subjective “truth” of our own experience.

How?

We do this by moving from the facts (bottom rung of the ladder, see image), to the facts we choose to focus on, to the meaning we give those select facts (informed by our biases, how we are feeling at that precise moment, and even whether or not we’ve had our lunch), to making assumptions, drawing conclusions, and forming beliefs (close to the top rung of the ladder).

Through this process, by the time we arrive at the upper rungs of the ladder, we have created an understanding of reality that is fairly unique to us (essentially, a collection of our beliefs). Based on that understanding, we take action. It’s happening constantly, in some form, for all of us, all the time.

- The basic idea: We live in a world constructed of self-generated beliefs.

Once we’ve formed a belief about a particular subject, we unconsciously seek data that reinforces our convictions.* This creates a feedback loop that further entrenches us in our beliefs. We are, in fact, built to do just that. (Nifty, right?)

The degree to which this negatively affects our ability to achieve results — particularly where our ability to do that depends on effectively collaborating with others — depends on our level of self-awareness with regard to this layered process of inference. When self-aware, we can manage ourselves well enough to see the ladder for what it is before taking action.

Without  self-awareness, we risk limiting our frame of reference. When that happens, we sell ourselves on the incorrect — or at least incomplete — version of events. That, in turn, limits our resourcefulness, creativity, and presence as a participant in a shared reality.

self-awareness, we risk limiting our frame of reference. When that happens, we sell ourselves on the incorrect — or at least incomplete — version of events. That, in turn, limits our resourcefulness, creativity, and presence as a participant in a shared reality.

Imagine if an entire organization of individuals were operating from the tops of their individual ladders of inference (e.g., from their beliefs instead of from the real observable data). Things could get pretty dysfunctional.

When we act on the belief that our view is the only viable view (and obvious to everyone else), we skip opportunities to bring others along to our way of thinking; we minimize the potential value in hearing differing points of view; and we diminish our ability to influence and to collaborate. An effective leader instead commits themselves to seeing with a wider aperture and understanding a broader view. A view that is in tune with what is likely to be more of a shared reality. Getting better at reality is something we’re working on here in the CCO.

“What the pupil must learn, if he learns anything at all, is that the world will do most of the work for you, provided you cooperate with it by identifying how it really works and aligning with those realities. If we do not let the world teach us, it teaches us a lesson.”

—Joseph Tussman

*This is an expansion on the concept of listening that was discussed in Lesson 1. Without examination, confirmation bias plays a significant role in keeping us climbing our own ladders of inference. Recall, there are many ways to listen (including habitual, factual, and empathic).